The process of formation of Afghanistan as a nation-state, with its current boundaries was initiated with the Treaty of Gandomak (1879) signed between the British Empire and the Afghan Amir, Yaqub Khan. It was when the responsibility of designing the foreign policy of Afghanistan was bestowed to the British. Later, during the reign of Abdur Rahman Khan (1880-1901), the boundaries of present-day Afghanistan were demarcated by the British and Russian empires to create a buffer zone with a minimal involvement of the Afghan rulers. The Treaty of Gandomak was also the first official agreement wherein the British Empire used the term Afghanistan to refer to it as a nation-state. This treaty also paved the way for the empire to strengthen its darling Amir – Abdur Rahman Khan – so that it can acquire control in Afghanistan by centralizing authority to the ruling families of Durrani tribe who were the rulers since Ahmad Shah Durrani. This consolidation and centralization of authority favoring British Empire would ultimately address its concerns of the rising influence of Russia in Turkestan.

Tracing back the history of modern Afghanistan to the Treaty of Gandomak and the reign of Abdur Rahman may not agree with the official Afghan narrative that sees the roots of modern Afghanistan in the consolidation of a kingdom by Ahmad Shah Durrani, who is also considered as the ‘father of the nation’. However, history shows that Ahmad Shah never strived for the consolidation of a country named Afghanistan. Mujib Rahman Rahimi in his seminal work – State Formation in Afghanistan: A Theoretical and Political History – discloses that Tarikh-i Ahmad Shahi (1773) written by Ibrahim Jami, Ahmad Shah’s court historian, does not mention the word ‘Afghanistan’ even once. Moreover, the same history book is quoted that Ahmad Shah considered himself as the ruler of Khurasan, having a much distinct boundaries as compared to present-day Afghanistan.

Rahimi’s work claims that the word ‘Afghanistan’ was first used in 1321 in Yaqub Herawi’s book – Tharikh Namae Herat – where it referred to a province of the Afghans (Pashtuns) located around the Sulaiman Mountain, not Afghanistan as a country. After Tharikh Namae Herat, the term Afghanistan is found in Tuzuk-i Taimuri and Babar-Nama referring to almost the same geographical location – area around the Sulaiman Mountain.

The notion of Afghan nationalism that claims that the Afghans (all the Pashtun tribes and all the ethnic groups) rose as a nation against the British Empire to safeguard the interests of its people is nothing more than a myth. The rulers in Afghanistan at the time of struggle with the British Empire for authority during the 19th century did not represent the people of Afghanistan as a nation. They, as mentioned above, belonged to the Sadozai and Mohammadzai families of Durrani tribe, which was one of the four main tribes among Pashtuns. Even they did not represent the Pashtuns as a whole because there were tribes among them that resisted the Durrani dominance; more interestingly, other families within the Durrani tribe itself resisted the rule of the mentioned families. Meanwhile, more than half of the population in the country consisted of Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Turkmens and several other ethnic groups, whose tribal leaders saw the dominance of Durrani rulers as that of the Pashtuns over their ethnic groups.

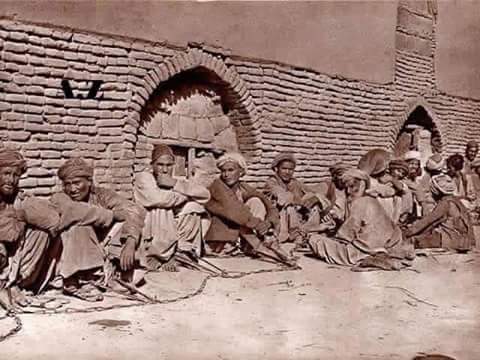

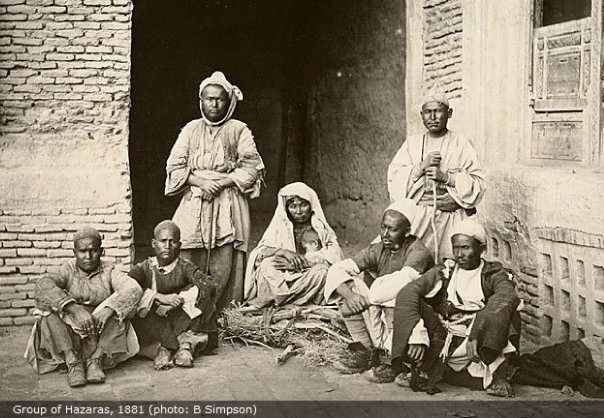

So, at the time of British intervention in Afghanistan, the country was a confederation of tribes, though the Durrani tribe among Pashtuns wanted to centralize and extend their authority based on the model of Ahmad Shah Durrani, they were facing resistance both from certain other Pashtun tribes and some tribes in other ethnic groups. When Abdur Rahman became Amir, and he strived to centralize authority and turn Afghanistan into a nation state, he came in confrontation with the tribes in Afghanistan that were individual units in themselves, had their own sphere of authority which they did not want to be challenged, and saw the state external to themselves. This resistance was further invigorated by the ethnic tensions prevalent among the Pashtuns and other ethnic groups, and in certain cases by the sectarian conflict, as Abdur Rahman used a strict Sunni version of Islam as the basis of his legitimacy, and considered Shi’ites infidels. As per the figures given by Thomas Barfield in his famous book – Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History – there were more than forty rebellions against Abdur Rahman, which he brutally crushed with the financial support of British Empire. Major among them were the resistance shown by the Ghilzai tribes, Hazara tribes in central Afghanistan (Hazarajat), Uzbek, Tajik and Turkmen tribes, Nuristanis and some others. The Hazaras among them were the receiver of the worst form of treatment, as Syed Askar Mousavi writes, “Massacre, slavery, heavy taxes and general destruction had reached such a level in Hazarajat that the very existence of Hazara people was endangered.” Crushing all the resistance provided Abdur Rahman and his sponsors a temporary authority and stability, but left permanent bloody marks on the history of Afghanistan, which kept on resulting in tribal clashes and ethnic strife. Moreover, his efforts were never able to create a comprehensive notion of nationalism in Afghanistan; neither, they were able to form a stable and functioning state in the country. In the words of Amin Saikal: “Repression, isolation and reliance on financial assistance from abroad at the cost of sovereignty were his trademarks, not comprehensive modernization and nation-building.”

Abdur Rahman’s efforts for a so-called nation-state were never meant to integrate the plurality in Afghanistan through diplomacy, negotiation or legitimate force; rather, they were vehemently violent and brutal and meant to enforce Afghan nationalism on the entire society through every possible mean, mostly setting the worst examples of human rights violations and annihilation and insult of unarmed communities. Unfortunately, the same concept of the nation-state was continued and further strengthened by Habibullah Khan (1901–1919) and Amanullah Khan (1919–1929), under the patronage of British Empire. It was actually the time when the official narrative of the Afghan nationalism was promulgated through the literature and organizations sponsored by the Durrani elite.

From the above discussion, we can draw certain important conclusions. First, the efforts for the establishment of a nation-state in Afghanistan started through the intervention of the British Empire in the country; they were never conscious and united efforts on the part of decentralized tribes and ethnicities in Afghanistan. Second, the concept of Afghan nationalism, being led by Durrani tribe, was enforced by Abdur Rahman Khan on all the Pashtun tribes and other ethnic groups through unprecedented violence. Third, an official narrative was later constructed based on the same flawed notion, which kept on haunting the nation-state in Afghanistan. Unfortunately, after the US intervention in Afghanistan, a similar concept of nation-state was revived, and the state-building efforts were made on similar grounds. The results are evident as Afghanistan is suffering from an ineffective state, unstable political system, persistent ethnic conflicts, and burgeoning sectarian strife.

2 Responses

Marvelously penned down… The writeup flows eloquently with elegant simplicity and reads through like a novel’ story rather than some baffling historiography.

It is to the point in addressing all issue specific aspects of a long timescale with ease and still very deft in keeping it succinct and precise.

I am of the same opinion as the author on this particular topic. I think that he has done justice to the subject-matter by remaining impartial and rational, with abundance of reference quoting and following line of logic in expounding the truth’ and clearing the dust and rust of time and confusion regarding this case.

I would kiss his pen.

قلمت رسا و سبز باد۔

Abhi

Worth article based upon the history. If, I am not wrong, and allowed to suggest for the references, if not qoutted..

Comments are closed.